Every year, as the rains transform sunbaked roads into muddy rivers, a different kind of storm gathers across Nigeria.

Cholera, a ruthless bacterial infection, silently spreads through contaminated public wells, overflowing gutters and pit latrines.

Unlike the wars and famines that dominate headlines, this silent scourge claims lives relentlessly; hence, the need for a holistic approach to address it.

According to public health experts, recurring cholera outbreaks can be attributed to lack of access to potable water, which is essential for maintaining good hygiene practices, lack of continued surveillance even after outbreaks have ended, flooding and poverty.

Malam Ibrahim Isa’s experience is an excruciating account of the menace of cholera.

Rabi, Isa’s seven-year-old daughter clutched her stomach; her whimpers echoing through their cramped one-room shack in Maiduguri, Borno.

Isa watched helplessly as his daughter’s once-bright eyes dimmed with dehydration.

“It started with a few cramps; then came the relentless vomiting and diarrhea.

“We have nothing; no clean water, no proper toilet; how can I fight this invisible enemy,” he said.

His tragic story is common across the country; it reflects the devastating impact of poor sanitation and hygiene.

According to the 2021 WASHNORM III report, nearly 90 per cent of Nigerians lack access to complete basic water, sanitation and hygiene services; leaving millions vulnerable, particularly children and women.

The report indicates that cholera has been endemic in Nigeria since it first appeared in 1972.

It shows that the 1991 outbreak was the most severe on record; resulting in 59,478 cases and 7,654 deaths, a case fatality rate of 12.9 per cent.

The World Health Organisation (WHO)’s recommended benchmark case fatality rate is less than one per cent.

This rate represents the number of deaths as a percentage of the total confirmed cases, both alive and dead.

Rates of outbreak in Nigeria have mostly fluctuated between one per cent and about four per cent.

Dr Emmanuel Agogo, Director of Pandemic Threats at the Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics (FIND), explained the high fatality rate during the 1991 outbreak.

“The 1991 rate was high due to very poor sanitation and hygiene strategies.

“Little or no surveillance was in place; and there was no community engagement or education on the dangers of the disease,” he said.

Agogo explained the importance of a unified approach.

“A whole-of-government, whole-of-society approach is needed.

“We must involve multiple sectors and stakeholders to prevent, prepare for, detect and respond to public health threats like cholera,” he said.

Although, currently, cholera treatment is free in all government facilities, shortage of health facilities, illiteracy, lack of infrastructure for water supply and waste disposal and conflict, leading to overcrowded conditions for displaced people are also major predisposing factors.

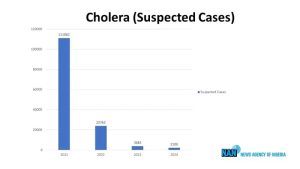

Data from the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (NCDC) reveals a grim reality.

“In the past four years (2021-2024), about 139,730 Nigerians are suspected to have contracted cholera, with a staggering 4,364 deaths.

Source: Nigeria Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (NCDC) https://ncdc.gov.ng/

“However, as of June 23, a total of 1,579 suspected cases, including 54 deaths (Case Fatality Rate of 3.4 per cent) have been reported from 32 states.

“Of the suspected cases since the beginning of the year, age group five is mostly affected, followed by the age groups five years to 14 years in aggregate of both males and females.

“Of all suspected cases, 50 per cent are males and 50 per cent are females.

“Lagos state (537 cases) accounts for 34 per cent of all suspected cases in the country, out of the 32 States that have reported cases of cholera.

“Southern Ijaw Local Government in Bayelsa (151 cases) accounts for 10 per cent of all suspected cases reported in the country,’’ the data indicates.

Available statistics further shows Bayelsa (466 cases), Abia (109), Zamfara (64 cases), Bauchi (46 cases), Katsina (45 cases) and Cross River (43 cases).

Others are Ebonyi (38 cases), Rivers (37 cases), Delta (34 cases), Imo (28), Ogun (21), Nasarawa (19 cases), Ondo (17 cases), Kano (13 cases), Niger (11 cases) and Osun (11 cases).

These account for 97.5 per cent of the suspected cases this year.

Comparatively, suspected cases of Cholera have decreased by 37 per cent compared to what was reported at Epi-week 25 in 2023.

More so, cumulative deaths recorded have decreased by 21 per cent.

In Nigeria, the availability of Environmental Health Officers (EHOs) can vary across the 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT).

During a cholera outbreak, EHOs are crucial for controlling the spread by ensuring proper sanitation, safe drinking water and effective waste disposal.

The impact of EHOs was evident during the Ebola outbreak in 2014.

While EHOs are generally present in all states, the effectiveness and reach of their work can be influenced by factors such as funding, infrastructure, and local government support.

In some areas, there may be shortages or limited capacity to respond adequately to outbreaks.

Efforts to control cholera often involve collaboration between EHOs, public health officials, and community organisations to ensure comprehensive coverage and response.

Principally, in the discussion around cholera, appropriate waste disposal becomes pivotal.

Mallam Kabiru Usman’s stall in Sabon Gari market in Kano exemplifies the sanitation challenges contributing to the outbreak.

The pungent odour of rotten vegetables mixes with the scarce, murky water used for washing – a stark reminder of the lack of clean water and proper waste disposal.

Usman’s story highlights just one aspect of the problem.

Open defecation, prevalent in rural areas like Bauchi, where Mrs Sarah Abubakar, a retired nurse resides, exposes individuals, especially women and children, to waterborne diseases like cholera.

The 2021 WASHNORM III report revealed a worrying rise in open defecation – from 46 million Nigerians in 2019 to 48 million in 2021.

Dr Amina Mohammed, a public health physician based in Kano, stressed the need for a multi-pronged approach.

“Cholera thrives in a web of neglect; we need immediate interventions like improved sanitation facilities in markets and slums, access to clean water, and a robust public awareness campaign.”

Mohammed pointed out the need for residents to work with local authorities to install handwashing stations at strategic points within the Sabon Gari market.

“Simple solutions like these, coupled with education on proper hygiene practices, can make a significant difference,” she said.

Dr Salman Samson Polycarp, an epidemiologist, stressed the critical role of market hygiene.

According to Polycarp, contaminated water and poor waste management can quickly escalate the situation.

He highlighted the lack of proper infrastructure in markets across the country as a significant factor.

Dr Jay Osi Samuel, a public health expert, warned of the dangers of improper abattoir management, where contaminated water can spread the bacteria far and wide.

Samuel explained the importance of strong public health surveillance to swiftly identify and address outbreaks.

“The fight against cholera is not just about battling bacteria; it is a fight for dignity, health and a brighter future for Nigerian communities,” he said.

Dr Jide Idris, Director General of NCDC, highlighted the need to address the root causes.

“Open defecation is a major challenge. It requires infrastructure and education. Building toilets is not enough; people need to understand why they must use them,” he said

He underscored the importance of local solutions and mobilising resources from state and local government levels.

Experts hold that the future of Nigerian communities depends on decisive actions.

Together, government agencies, healthcare professionals, NGOs, and ordinary citizens can turn the tide against cholera and build a healthier future for all.

People can be part of the solution by supporting relevant NGOs or volunteering their time to organisations working on sanitation projects and hygiene education in Nigeria.

Concerted efforts are required in the onslaught against cholera including raising awareness and sharing information about cholera prevention measures at family and community levels.

What’s more, it is critical to moblise local representatives to prioritise sanitation and healthcare initiatives.

Public health specialists say that synergy among Nigerians can break the cycle of cholera and ensure a healthier future for all.

(NANFeatures)