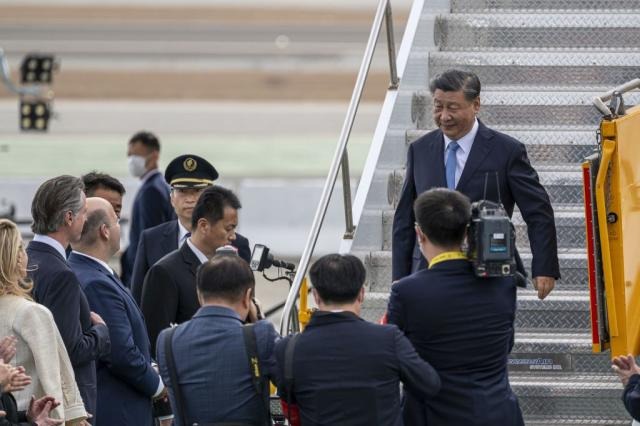

When Xi Jinping stepped off his plane in San Francisco yesterday for the Apec summit, it was in circumstances very different to the last time he landed on American soil.

When he was wined and dined by Donald Trump at Mar-a-Lago five years ago, Mr Xi was in charge of a China still on the ascendancy.

It had a buoyant economy outperforming forecasts. Its unemployment rate was among the lowest in years.

While consolidating his power for a second term, Mr Xi proudly pointed to China’s “flourishing” growth model as something other countries could emulate.

By then, cracks were already appearing in what he calls his “Chinese Dream”. They have only widened since then.

One view is that because of this, Mr Xi is in a more vulnerable negotiating position this time, though expectations of major breakthroughs are low.

After an initial bounce back, the post-Covid Chinese economy has turned sluggish.

Its property market – once a key driver of growth – is now mired in a credit crisis, exacerbating a domestic “debt bomb” that has ballooned from years of borrowing by local government and state-owned enterprises.

Many of these issues could be attributed to China’s long-predicted structural slowdown finally making itself felt – painfully.

In the last two years crackdowns on various sectors of the economy, as well as prominent Chinese businessmen, has caused uncertainty.

This has recently widened to include foreign nationals and firms, heightening worries in the international business community.

Foreign investors and companies are now moving their money out of China in search of better investment returns elsewhere.

Youth unemployment has skyrocketed to the point that officials no longer publish that data.

A fatalistic ennui is spreading among young Chinese, who talk about “lying flat” or leaving the country in search of better prospects elsewhere.

Mr Xi is also struggling with issues within his carefully-constructed power structure.

The unexplained disappearances of key members of his leadership team and military top brass could be seen as either signs of pervasive corruption or political purges.

Some observers have contrasted China with the US, whose economy has weathered the post-Covid recovery better.

Until recently, Americans may have feared the day China would overtake them as the world’s largest economy, but now analysts doubt if this will happen.

China’s current economic challenges will be an “important factor” in Mr Xi’s negotiations and “would lead to a stronger desire to stabilise the economic, trade and investment relations with the US”, Li Mingjiang, an associate professor at Singapore’s S Rajaratnam School of International Studies, told the BBC.

“Mr Xi will want to receive reassurance from Mr Biden that the US will not expand its trade war or tech rivalry, nor take additional measures to decouple economically.”

Beijing has complained vociferously about the US imposing tariffs on Chinese imports, blacklisting Chinese companies, and restricting China’s access to advanced chip-making tech.

The fact they are meeting in San Francisco, home of Silicon Valley and the world’s leading technology companies, will not be lost on the two leaders.

There is speculation they may announce a working group to discuss artificial intelligence, which the Chinese reportedly hope to use to persuade the Americans not to further extend US technology export restrictions.

With Taiwan’s election round the corner, which has the potential of becoming a flashpoint, Chinese officials have made it clear they want the US to steer clear of supporting Taiwanese independence. But the US has repeatedly emphasised its support for the self-governed island in the face of Chinese aggression and claims over it.

Taiwan remains a dicey tightrope for both countries.

US officials are also seeking a resumption of military-to-military communications and Chinese cooperation in stemming the flow of ingredients fuelling the fentanyl trade in the US – and there are already reports that the Chinese will agree to these.

Chinese state media has pressed pause on the US-bashing, releasing a raft of commentaries extolling the merits of resetting relations and working on cooperation.

There is talk of “returning from Bali, heading to San Francisco”.

This is a reference to the last time Mr Xi and Mr Biden met in person – at the G20 Bali summit almost exactly a year ago – which marked a high point in recent US-China relations before plunging to the nadir of the spy balloon incident.

“The propaganda preparations for the Xi-Biden meeting this week are making it clear it is okay to like America and Americans again… I think you could make the argument the propaganda 180 makes Xi look like he is quite eager for a stabilised relationship because of at least economic if not also political pressures,” China analyst Bill Bishop wrote this week.

Mr Xi also appears equally, if not more, keen to woo the US business community.

The BBC understands he will be the guest of honour at a ritzy dinner on Wednesday night organised especially for him to meet top corporate executives.

In what could be a sign of his true priorities, Chinese officials had initially demanded the dinner take place before Mr Xi’s meeting with Mr Biden, according to a Wall Street Journal report.

But the Americans should also not expect Mr Xi to be arriving hat in hand and eager to please.

Many believe mutual suspicion will endure and the two leaders will not likely remove existing trade and economic roadblocks put up in the name of national security.

Mr Biden has preserved many of the Trump-era sanctions aimed at China, while initiating and then deepening the chip tech ban.

Meanwhile Mr Xi has enacted a wide-ranging anti-espionage law, which has seen raids conducted on foreign consulting firms and exit bans reportedly used on foreign nationals.

The two sides are also likely to not budge on “core interest” issues such as Taiwan and the South China Sea, where Beijing continues to build up its military presence to defend sovereignty while Washington does the same to reinforce its alliances in the region.

Faced with the need to “not appear weak” to the US, Dr Li says, “it’s a difficult balance that the Chinese leadership has to strike – between the objective of seeking a more stable and positive relationship with US on one hand, and also appear to be strong and resilient against some of the American pressures.”